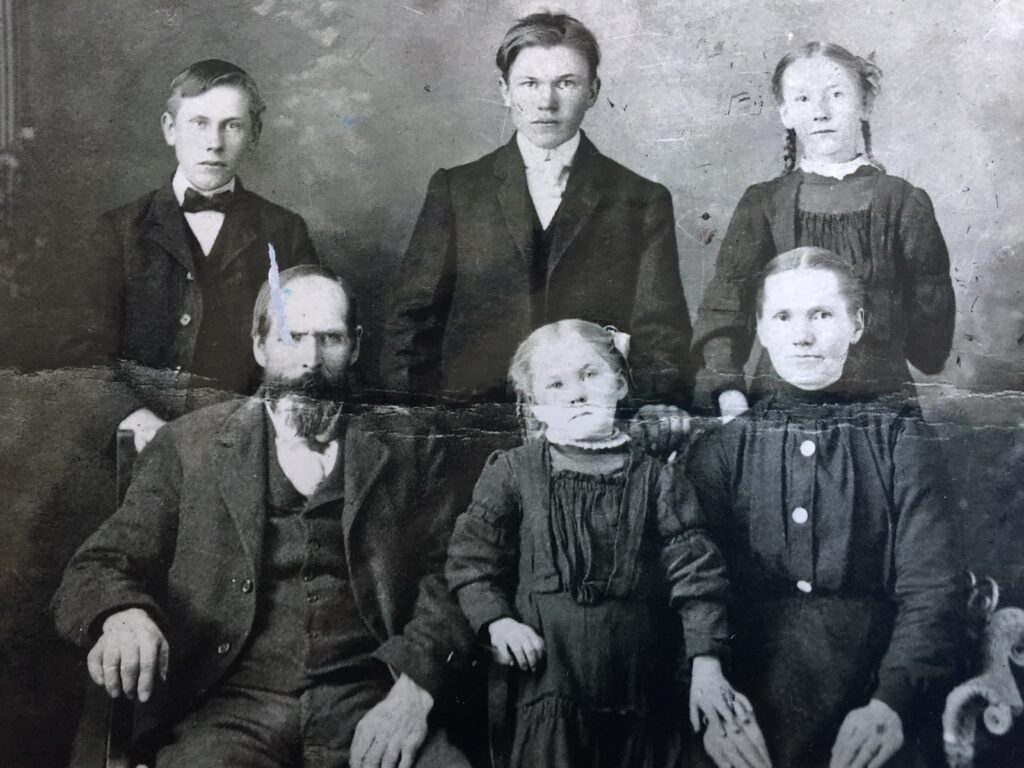

Pictured here the immigrant Anderson Family: Bottom row – Lars, Mabel, and Lisa; Top row – Mathew, Levi, and Alma

The Mystery

Even as children, my siblings and I knew we were mostly Norwegian. (We must have known we were legally Americans, but we never called ourselves that.) Our mother’s father (morfar in Norwegian) came from Norway as a young man, and the parents of our father’s grandmother (farmor or father’s-mother in Norwegians) had come from Norway as well. That made us three-eighths Norwegian, nearly half.

But we also said we were a number of other things – significantly Swedish. Mom’s mother (our mormor or mother’s mother) must have been Swedish because Grandma Mabel’s parents had both come from Sweden and she herself had written in both Swedish and English. We knew that from her notebooks, which were about all we had of Grandma Mabel. She died at 24 when Mom was just over a year old.

“But where in Sweden did Mabel’s parents come from?” Mom had asked. No one answered. “At least her father wasn’t a Finn,” one relative said. As if that explained. As if being Finnish would have been bad.

In truth, that odd statement only raised the suspicion (or the hope) that perhaps he had been Finnish. When we kids were growing up, our family moved to northeastern Minnesota where we lived among many Finns. They were our friends; we admired them. Mom, especially, wished she were part of that Finnish community.

Just before the death of our step-grandma, who had been a cousin to Grandma Mabel, she told Mom that that Grandma Mabel’s father had actually been “a heathen Lapp.”

Could it be? Might we have a Sami ancestor?

How could it be that we knew so little about our grandmother and her parents?

The Search

Last January, my sister and I decided to tackle the question directly. We knew that Grandma Mabel had married Grandpa Olaf in northwestern Minnesota. Grandpa Olaf had immigrated from Norway in 1908 and become part of a community of recent arrivals from Sweden and Norway who worshiped together in home churches. Oddly, none of them were Lutheran. Why, being Swedes and Norwegians, didn’t they join the Lutheran immigrants? We didn’t know.

None of our relatives had mentioned a Swedish place name; our ancestors’ graves and their relatives’ and neighbors’ graves’ said only “Sweden.” Census records said the same. Common family names – theirs being Anderson and Olson – where not easy to link from immigrant ship manifests list to particular immigrant people.

A month into our search for our great-grandparents’ past, my sister and I were still coming up dry. We’d provided DNA samples. We’d signed up on Ancestry.com and FindaGrave.com. We’d recorded all the names and the dates and the few other details we knew. There were no more leads.

Perhaps, we thought, we should just stand respectfully outside the locked door of our probably Swedish/maybe Finnish/maybe Sami great-grandparents’ histories and let them rest in silence. They must have had their reasons to hide.

And then, the very next day, like a sending from the otherworld, a message popped up on Ancestry. It announced that enough of our family had submitted DNA so that Ancestry could state with assurance that our mother had no Swedish blood.

None. No Swedish blood.

Genetically, the message said, she was a tad more than half Norwegian and a tad less than half Finnish.

After walking about for a day in stunned mind-shifting thought, we began to research how it could be that people coming from Sweden in 1880 and speaking only Swedish could actually have Finnish DNA.

Ancestry.com provided us a place to start – Grandma Mabel’s parents, Lisa Olson and Lars Anderson, had both come from a place called Torsby Commun. We found it on a map; it was a short distance across the border from the part of eastern Norway where our grandpa had grown up.

I called my Norwegian second-cousin who also grew in that part of Norway.

“We just learned that our mother’s grandmother came from Torsby in Sweden,” I told him. “She wasn’t a Swede at all. She was a Finn.”

“Ah, Torsby,” he said. “I know it well. It’s where the Finns settled back in the 1500s when the king of Sweden invited them to come farm. But the Swedes were never happy about Finns being there. The area is called Finnskoga – Finn Forest. Those Finns practiced a slash and burn farming and had a special kind of rye that almost died out. And they were a mystical bunch. I’ve seen their buildings in the part of Norway where I grew up because they came there too. They painted runes on their buildings to protect them.”

Finns! Why wouldn’t anyone tell us this? And then I remember my step-grandma saying, “At least he wasn’t a Finn.”

He was. And so our great-grandma. And so was our grandma. And so, significantly, was our step-grandma herself. Didn’t she know? Or was there a reason she was claiming to be something else?

Getting the Facts

After that, we found general information easily. In the 1500s the king of Sweden did indeed invite Finns to come to Sweden to plant Svedjebruk rye because its yield was 100 grains for each grain planted and because they would live in spruce and birch woods that Swedes tended to avoid. Many came, our 16th century ancestors among them. They were called Forest Finns and lived in Finnskoga, “The Finn Forest,” the dark forest stretching across what is now the border between Norway and Sweden.

But they didn’t mingle much with the Swedes. From the 1500s to 1880 when my great-grandparents settled in Minnesota, they had children only with other Finns. Four hundred years and no mixing of Finnish with Swedish blood occurred!

There was, in fact, severe oppression. In Sweden the Finnish language was outlawed; one decree said that Forest Finns could be killed and their houses burned if they refused to speak Swedish. They could be put in jail for reading their own books (which indicates that they had books, not surprising because even then Finns were 90% literate). They could be fined if they lingered in town for more than an hour after attending church services.

However, it was necessary that they attended the Swedish Lutheran church. If they were not baptized in that church, they did not legally exist. If they were not confirmed – and for an individual to be confirmed she or he had to read and write in Swedish – their marriages and children would not be recorded.

Swedish people said they stank from the smoke in their buildings; the Finns, in turn, thought the Swedes and Norwegians were dirty to bathe in filthy water instead of cleaning themselves in the sauna. Swedes and Norwegians doubted Finnish morality since Forest Finns took sauna together, women and children and men; outsiders didn’t understand the strict rules that were held to in the bathhouse.

Even their way of farming, a method that worked well in sparsely populated areas, was outlawed; the new Swedish iron-smelting industry demanded the timber be used instead for charcoal and underpaid the now-impoverished Finns to produce it at artificially low prices.

The pressure to conform to the dominant cultures, either Swedish or Norwegian, was intense.

Yet the Finns held onto their Forest-Finn dialect, to their lives in the woods, to aspects of their culture. Some managed to speak their own dialect until the second half of the 20th century when the last two speakers of it died.

Could it be that our great-grandparents spoke Finnish as well as Swedish?

Great-grandpa Lars must have known he was Finnish. He lived in Finn Forest and his family names were Hyattien Rosenmark and Multainen. We found those names once we could locate birth records in Sweden. Any northern Minnesotan would recognize them as Finnish! Great-grandma Lisa had to know too. Her father’s family name was Moijainen, and her mother’s were Kymöinen and Räisäinen.

We could gather these facts in part because Norway instituted an early census of all the Forest Finns – an attempt to control them and keep them separate. While the impetus for the census seems oppressive, it has benefitted us. We’ve been able to find probable records going back to Finland in the 1500s.

In spite of the pride that the Finns in Sweden seemed to exhibit, when my great-grandparents arrived here in 1880, they claimed that they were Swedes. They dropped any Finnish-sounding names. They called themselves after their father’s first names – Anderson and Olson – not even maintaining the Pålsdotter form that Lisa had had as one of her names in Sweden.

The name change is understandable. Grandpa had been Kristiansen in Norway, but he picked the place name “Viken” (meaning “the bay” and indicating that the family lived on a bay of Lake Mjøsa) when he immigrated. Viken got changed to Wick when he landed. A major goal of many immigrants was to fit in at the new land.

Then also – having been so long persecuted in Sweden, maybe Lars and Lisa, our great-grandparents, hoped things would go better for their children if they were thought to be Swedish.

Then also – are you really a Finn if you can’t speak the language and if you and your parents had never once set foot in Finland? Probably no Forest Finns could hope to be accepted by Finns who came directly from Finland.

Where Might the Search Lead Next?

Our appetite to learn any possible wisdom from this past has been wetted. Yes, someday we may visit Finnskoga.

Until then, we’re gathering the history available. Two women – Åsta Holth (herself Forest Finn) and Britt Karen Larsen (a Norwegian academic who researched Forest Finn life) have written novels depicting the lives of Forest Finns. With a Norwegian friend, I’ve been translating some of these books into English, going so far as to check with the Norwegian presses to see if we can make the translations public.

Of course, what we really need is to learn a form of Finnish that no longer exists. Maybe a close approximation would be to learn Finnish as it is spoken now.

In the first book of her Finnskog trilogy, Åsta Holth says that, one day, a kindly vicar let the people read in their own language. She wrote, “They stood up in their chairs, pale and solemn, and read together in Finnish. The elders had tears in the furrows of their cheeks. The last time they had read these words or heard their parents read them, it was in the old land – fifty, sixty years ago. The heart ached at the memory” (our translation).

Perhaps some readers of this article know more about those memories. Perhaps some want to learn with us. The Swedish Finn Historical Society has offered to host an online gathering of those of us who may want to meet to share stories and resources.

Might you be one who wants to join in that group or to learn with us in some other way? If so, write to me at ranae@ranaehanson.com.

Note: This article was written for the Swedish Finn Historical Society and will also be published on their web page. I thank them for the impetus.

Sources

Edimentals. “The Svedjurug Story.” https://www.edimentals.com/blog/?p=9904

Holth, Åsta. Kornet og Freden. Gyldendal, 1955.

Inktank. “How Finnish Immigrants Helped Build America” https://inktank.fi/china-swedes-forest-finns-and-the-great-migration-how-finnish-immigrants-helped-build-america/

K12Academics. “Education – Finland.” https://www.k12academics.com/Education%20Worldwide/Education%20in%20Finland/history-education-finland

Larsen, Britt Karin. Det Vokser et Tre i Mostamägg. Cappelen Damm, 2009.

Northernbush. “Swidden, svedjebruk, and slash-and-burn cultivation.” https://northernbush.com/swidden-svedjebruk-and-slash-burn-cultivation/

Wikipedia. “Forest Finns.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forest_Finns

Great story!! I look forward to more progress and hope that I can help both of you!!

Thank you for this! So much of what you describe fits my great-grandfather’s background. I didn’t know he was a Forest Finn until I did DNA testing. We always assumed he was Norwegian. Well done!