My great-grandparents may never have said they were Swedish. Perhaps they said nothing more than that they came from Värmland County in Sweden and, standing back in silence, let others assume. The others were the ones who told me my grandma was a Swede from Värmland. None of them mentioned that Värmland was the forest area of the Finns.

But now, having discovered that my grandmother’s parents were actually Finns whose families had lived in Swedish forests for four hundred years, I yearned to learn who the Forest Finns were.

Quick searches offered tantalizing details. For example, when the Finns were moving to the new forests of the Swedish-Norwegian borders in the 1500s, they sent their sons ahead to find farmable sections of spruce. When a young man would find an area, he’d climb the tallest spruce and there knit the family’s banner. After hanging it in the tree, he’d climb down and walk back to the family while composing a poem about his path and its turnings. He’d then lead his family along the path he had come by reciting the poem in reverse. When they arrived at the tree with their pattern hanging in it, they would stop. Could that be more than fantastic story-telling? This next bit certainly is true: The first permanent building they would erect was the sauna.

They would live off what the forest provided while they girdled the spruces the first year and burned them the second. Then, they planted rye and turnip, spinning in circles, some say, while spitting the seeds from their mouths into the still-warm ashy earth. The third year, they’d be able to feast on rye. After a few years the forest would grow back, nourished by the ash and the dung from small Forest Finn cows.

Who wouldn’t love such a people? Who wouldn’t claim descent from them?

Uncovering the Cover-up

But something happened between the 1500s and 1880 when my great-grandparents traveled by ship and train to Minnesota. For centuries they had held to their Finnish dialect, their Finnish place names, and their saunas, mingling rarely with ethnic Swedes.

How did they lose their language and turn up in Minnesota speaking Swedish, saying nothing about any kinship with Finland?

In Norway two women have recorded the stories of these people. Åsta Holth, herself a Forest Finn, wrote one trilogy about her father’s ancestors and one about her mother’s. Britt Karin Larsen, a Norwegian poet and national scholar, researched Forest Finns, interviewing those who still lived in Sweden and Norway in the twentieth century. She wrote a series of seven novels about them.

Holth’s novels were published earlier, so I started with those, but my Norwegian isn’t good enough for me to just sit, turn pages, and take in the scenes. To “read” I had to translate. To translate Holth’s novels I needed help because the dialect they are written in isn’t one that is commonly taught.

[An illustration here of the challenge: In 1971 when I visited the eastern part of Norway where my grandpa grew up, my second cousin took me and a Norwegian friend to visit a woman in the mountains. She baked us heart-shaped waffles on an iron thrust into her fireplace. She spoke as she flipped the griddle in the flames. My Norwegian friend shook his head in bewilderment; though he knew both official forms of Norwegian, he could make sense of her words. My cousin translated to him and then he translated to me. The waffle-maker had explained that her batter contained only eggs, cream, and sugar. By the way – they were delicious with her hand-milked cream and hand-picked berries! But to the point – the waffle-maker’s dialect was like Åsta Holth’s.]

A Norwegian friend came to my aid; we’ve translated the first of Holth’s novels together – Crown and Freedom (1955, Gyldendal). What a wealth of information it offers! A few bits: The sauna was the first building built on each farm and was the purest, the most sacred built structure to which one came for birth and death as well as cleansing. The first tree planted on a farm would grow and thrive with the family and was expected to falter if the family’s fate declined. Women’s work included care of cows and goats and horses, carding of wood, spinning and weaving, gardening, growing flax for linen, cooking and preserving, mending, gathering medicinal plants and doctoring, and companioning men in all their work. Clothing was often made from animal hides; baskets and shoes and hats and roofs were woven of birch bark; buildings were heated by stone fire places without chimneys but with hatches to let out the smoke. Farms were sometimes passed to the eldest daughter. The Finn’s closest companions were animals. After a century or two, Finnish fire-based farming was banned in Sweden so the forests could be cut and turned to charcoal to feed the new iron foundries and also to force the Finns off their farms and into the iron mines and mills.

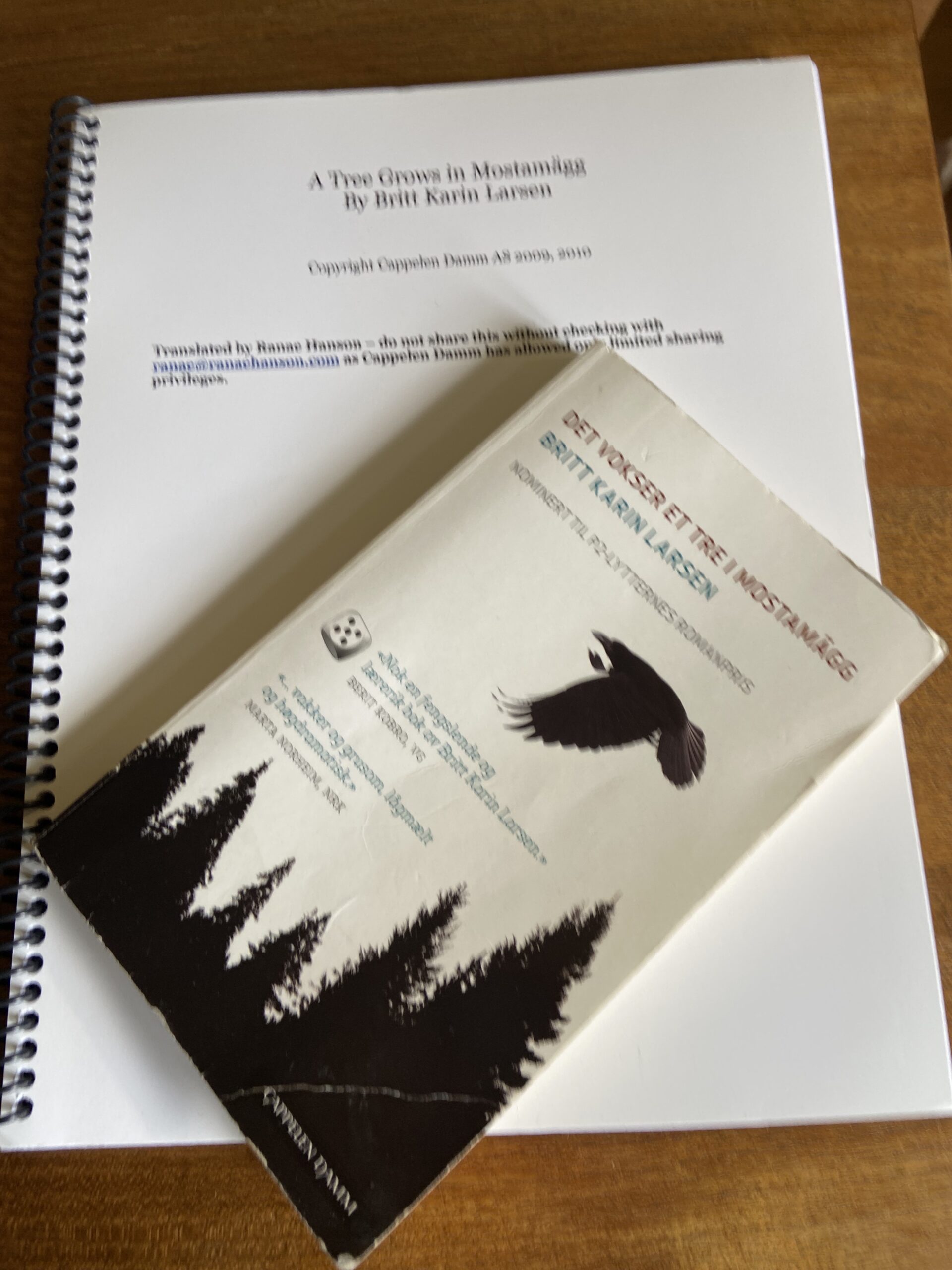

Larsen’s more modern novels are written in a Norwegian that I can translate myself. Clearly she has read Holth’s work. Moreover, she’s a master of plot and a musician with sentences. I’ve translated her first two novels, A Tree Grows in Mostamägg and Sky Bear’s Forest. The characters have become my friends. Because the Forest Finns were a relatively small group of intermingled families, I can see how these lives paralleled those of my relatives.

Who They Were

What have I learned? That these people lived in close communion with the earth and its trees, rocks, waters, and moving beings. That bears, for example, were thought to have come from the sky and were to be treated with respect even when they were killed and that they would return to the sky after death. That the Finn’s nature-based mindset came into conflict with the type of Lutheranism forced on them by the surrounding culture. That in order to be registered as existing, they had to be baptized as Lutheran and then confirmed – and to be confirmed they had to speak and read Swedish. That Swedes felt Finnish was too difficult to learn and that the Finns themselves were dirty because their clothing often smelled of smoke. That the Finnish sauna was a sacred space and bathing a time for no loud talking, no lowly thoughts or lascivious looks, but that the Lutheran priests were deeply troubled that the Finns took sauna with the whole family, all of them naked, and, therefore, the priests assumed, all of them depraved. That Finns in the forest barely scraped by, a good number dreaming of moving on again – this time to America. That the prejudice against the Finns often became internalized in them; that they hoped a girl might escape by marrying a Norwegian or that a family might cross the ocean and be able to pretend to be a people less despised.

I’m on a quest. Never have I felt at home on this earth the way I do now after discovering who my mother’s people were and how they came to settle on Ojibwa land.

In planning for a trip to visit the Finn Forest, I’ve been in email contact with Britt Karin Larsen herself. She raised the question in a message about which Forest Finn family I might be descended from. What a jolt! Could I really be part of a family that extends back in time and knew its roots to be in the earth, a family that sat together silently in a sauna?

I have begun to find answers to the questions that pushed me into this quest—

-Why is silence held, sometimes for good and sometimes to cover a troubling secret?

-Why did my immigrate ancestors leave their homelands and settle in the homelands of the Ojibwa?

-How does the prejudice against and marginalization of my ancestors help me understand genocide and racism today?

-What practices and attitudes did my ancestors hold that could provide better paths through our current ecological and justice challenges?

Do similar questions nudge you toward your own ancestral roots? If so, consider letting me hear of your search.

Thank you Ranae for your stories!!

So interesting to learn this, cousin Ranae! I want to hear more. I’ll pass this on to my sons, who have Finnish ancestors on both sides & Ojibwa on their Dad’s side. Thank you!