Here at the lake, we live as part of a small watershed.

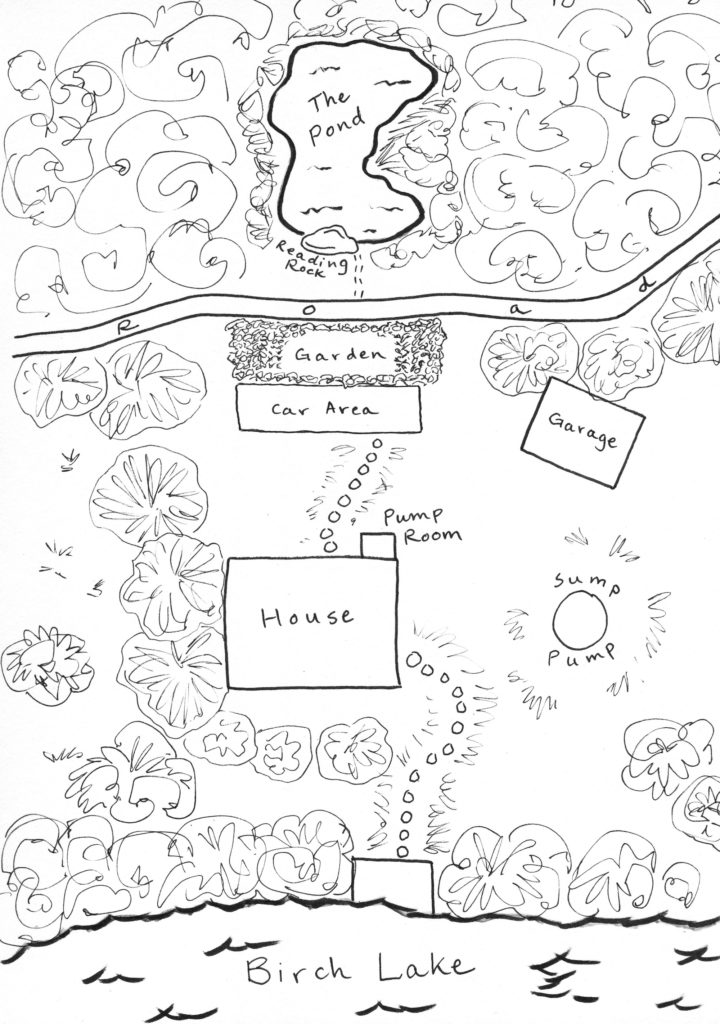

The water we drink fell some time ago as rain or snow and landed quite close by. Some of it fell directly into what my family calls “The Pond.” If you walk to the pond from our house, the trek takes all of five minutes. In forty-five minutes with good boots and a willingness to push through the bracken or reeds at water’s edge, you can make your way around the wider main body and then both bays of the kidney-shaped pond and arrive back at our yard. The Pond isn’t big, but it’s huge with life.

On regional maps The Pond is called Minnow Lake and is, actually, the last water receiver from a chain of fens. Fens are footprints from the age of glaciers. When the glaciers receded, they left various chunks of ice in the ground. As those clumps slowly melted, their holes became ponds and then, over the ages, filled in as swampland. The other indentations in our chain are cattail bogs, the one nearest the pond with a narrow ring of open water circling it.

Rain or snow that falls onto even the furthest east of our fens eventually makes its way past lily pads, through water bugs, and to Minnow Lake itself, which is the lowest lying of the small earth indentations. There the water supports ducks, fills the lower floors of the beaver lodge, provides sustenance to resident rabbits and deer and wolves.

I drank directly from the pond on occasion in my teen years when I got thirsty after reading on a rock that rose up above the water below. That rock has a hollow perfectly sized for a body, contentedly curled with a book. The brush between the pond and the road and the trees rising above ensure a private nook—private but for the black birds, the crows, the chickadees, the sparrows, the spiders, the dragonflies, and gnats.

Most humans would not drink directly from the pond. Still, it is clean. The bottom muck filled with busy bacteria and other mysterious lives keeps it healthy. No one spreads insecticide or fertilizer nearby. No farms adjoin these waters to feed them with damaging runoff. I suppose the beaver pee into it, but then, if deer can drink from the pond, why can’t I?

We do not carry water for the house directly from the pond; the earth does the transporting for us. Pond water seeps through the layers of mud, down past the rocks and gravel below. It travels through multiple layers of microbial cleaners. Deep down, about twenty-eight feet below, it enlarges the water table and flows toward us under our little road. It crosses under the garden. It comes in one clear flow right beneath the house.

There some of it is intercepted by the sand point, the tip end of the well that my dad drove down eighteen feet some sixty years ago. The pump in our basement is housed in the appropriately-named Pump Room, a small brick-lined room that sits like a nubbin off the basement itself.

When I open a faucet in the kitchen, the water comes up from the Pump Room, straight from the Water Table, directly from the depths below The Pond.

We’ve had it tested. Perfect, 7.1 pH, almost no minerals. Better than any water from any town we know of. And it’s sweet.

I wish everyone could drink water so pure.

We don’t drink it all, of course. Only a bit of the water in the Water Table comes up our pump. Most of it keeps flowing under the foundation and then out at the bottom of the hill the house is built on. When I leave through the basement door on the lake side of the house, and take thirty-one steps on a combination of path, stone steps, and wooden stairs, I am level with the emergence of the water.

It seeps out as The Springs, trickles of pure, cold water. The Springs make the rest of the shoreline—twenty more steps for me to reach the lake—a mucky host for JoePye Weed, Marsh Marigold, Star Flower, sedges, mosses, ferns, and, rising above, Tamarack, White Cedar, White Spruce, Balsam Fir, and Birch.

And then the water flows into the lake. Birch Lake flows twenty-one miles toward the east and then into the Kawishiwi River, and that flows into the White Iron Chain of Lakes, and that flows north to Hudson Bay.

But, of course, there is the water we drink to account for. It also is part of the watershed. In due time, after we drink it, we shed it.

That shed-water goes down our drains and into the septic pipes to the west of the house where, for the last thirty years, a sump pump has pumped it up the hill to a drain field under the garden. There it washes through a field of pipes laid about three feet under the surface. Bacteria and other helpful microbes use the refuse in it for their own life-support fuel, and, doing so, they clean it. It seeps down through small holes in the pipes and drops through the layers of gravel, which scrub it further. It joins, once again, the Water Table.

Before falling from the sky and after leaving Hudson Bay, this water is one with all the rest of the water on earth.