One of the first words I learned in the Duolingo Finnish course was velho. Duo translates the word as “wizard,” but the sentences give a better indication of the meaning.

– “We love our wise velho.”

– “The Swede is a Viking and the Finn is a velho.”

– “The shaman is Sami, and the velho is Finnish.”

– “The velho walks through the quiet forest.”

The Finnish word has no indication of gender and its connotations are always positive.

A Finnish velho is wise and in the forest.

In the Norwegian novels about Forest Finns, the men and women who know the old ways – who can cure with herbs, for example – are called trolls. In Finnish, they would have been velhot, the plural form of velho.

How should I translate that name of one who followed the old ways, who knew which plants could cure pain, who knew words to address emotional distress, who could pass on the old stories?

Shall I call them “witch” – as people did to excuse burning and drowning of humans? Often, evidence shows, those murdered people were midwives and healers, or simply odd people, so possibly they were velhot. Some, I learned from the film Burning Times, had the simple oddity of one blue and one brown eye.

Shall I call them “wizards”? Harry Potter is not what I want to indicate. So, what about “sorcerer”? I see dancing brooms and magic wands.

These are not velho.

What about the Norwegian word “troll”? Nowadays, that word can imply a boulder-sized, hunchbacked lump, a being who dwells in subterranean caves.

So, for now, I will simply call her/him/them velho. The big rocks they honored (worshiped near) were called “trollkirker” or “troll churches” in Norwegian.

In Britt Karin Larsen’s novel about Forest Finns, A Tree Grows in Mostamägg, both Kaisa (an aged woman) and Noppis-Matti (an aged man) are called trolls by other characters. Kaisa is said to know “the other book” as well as the Bible that she frequently quotes. She is sought out for medical and emotional cures. She offers both herbs and sound psychological advice. Her godson, Jussi, says she must be a troll because she has a pouch around her waist in which, people say, she caries graveyard soil to empower curses. When a bear kills a cow, the farm people accuse Kaisa of having overpowered the bear and forced it to take the cow. Actually, Kaisa only has coins in that pouch that she hopes will eventually pay someone to carry her body after death to burial in the Christian churchyard. Kaisa is the one people come to, sometimes secretly, when they need help. But, at other times they renounce this troll-elder, their velho.

Kaisa, like everyone else in the forest, is acquainted with the troll pine where people push wooden stakes into the bark to ask for blessings or salvation from accidents. She also knows how it can be used to curse someone. Once, after her husband had become drunk and neglected their child so badly that the child walked off and died by sinking into a bog, she made a “pine knot” with some of his clothing and threw it into a stream. She wished on the knot that he would not be able to make any more children. Because he died soon after that, Kaisa is internally tormented, even though she knows she had not wished for his death. She accuses herself – was not death a possible answer to a wish that a man make no more children? She asks that God forgive her for that wish.

Britt Karin Larsen, the author, spoke to many Forest Finns to get authentic reports of their lives. She presents Kaisa as wise, clear-headed, and complex.

Kaisa, like most Forest Finns, is both a Christian and a follower of traditions that honor the natural world. She attempts to bridge between those Finnish ways and the Swedish culture encircling her people. She fervently urges younger Finns to conform to the demands of the Swedish Lutheran church. She spends her meager savings and her physical energy to get young people educated in Swedish, even giving the money from her burial pouch toward her godson’s education. Kaisa quotes the Christian scriptures and trusts them, insists on the “Our Father” being prayed, and urges parents to get their children confirmed. She does this both because she is a convinced Christian herself and because she believes that conformity to the official church in Sweden could help those children survive. Her own child died. She refuses to accept the deaths or the persecution of other children.

I think that she also uses the dominant religion as a way to cover over and protect the older customs she adheres to. Inside her, both are honored. Forest Finns arrived in Sweden as Christians who had no difficulty being both Christian and people who honored and were one with nature. But for Kaisa, there was conflict between the Christianity of the Swedish church and her unity with nature. She ponders. She suffers. She holds her distress privately because she is the responsible elder.

With that, I arrive at a possible partial understanding of my own Forest Finn ancestors. The fictional Kaisa is of the same time period and place as my great-great grandmother Marta. My great-grandmother Lisa and my great-grandfather Lars would have been young people with elders like Kaisa around them.

Were any of these ancestors also velho?

Starting nearest to me, I see Kaisa’s dual authority in my own mother. She was a gardener, a gatherer of herbs, a healer. She was also a fervent Christian. So determined was she in both of those things that she pushed Christianity and herbs down people’s throats (literally in the case of “green drink”). She was called a “health food fanatic” and a “quack.” These are kinder words for something similar to “witch.”

Where, I have wondered, did Mom learn to garden and pick berries, to can, to plant and forage herbs? Her mother couldn’t have taught her because she died before Mom was two. Her step-mom didn’t allow Mom to mess up their family yard with a garden, also wouldn’t let Mom have a pet.

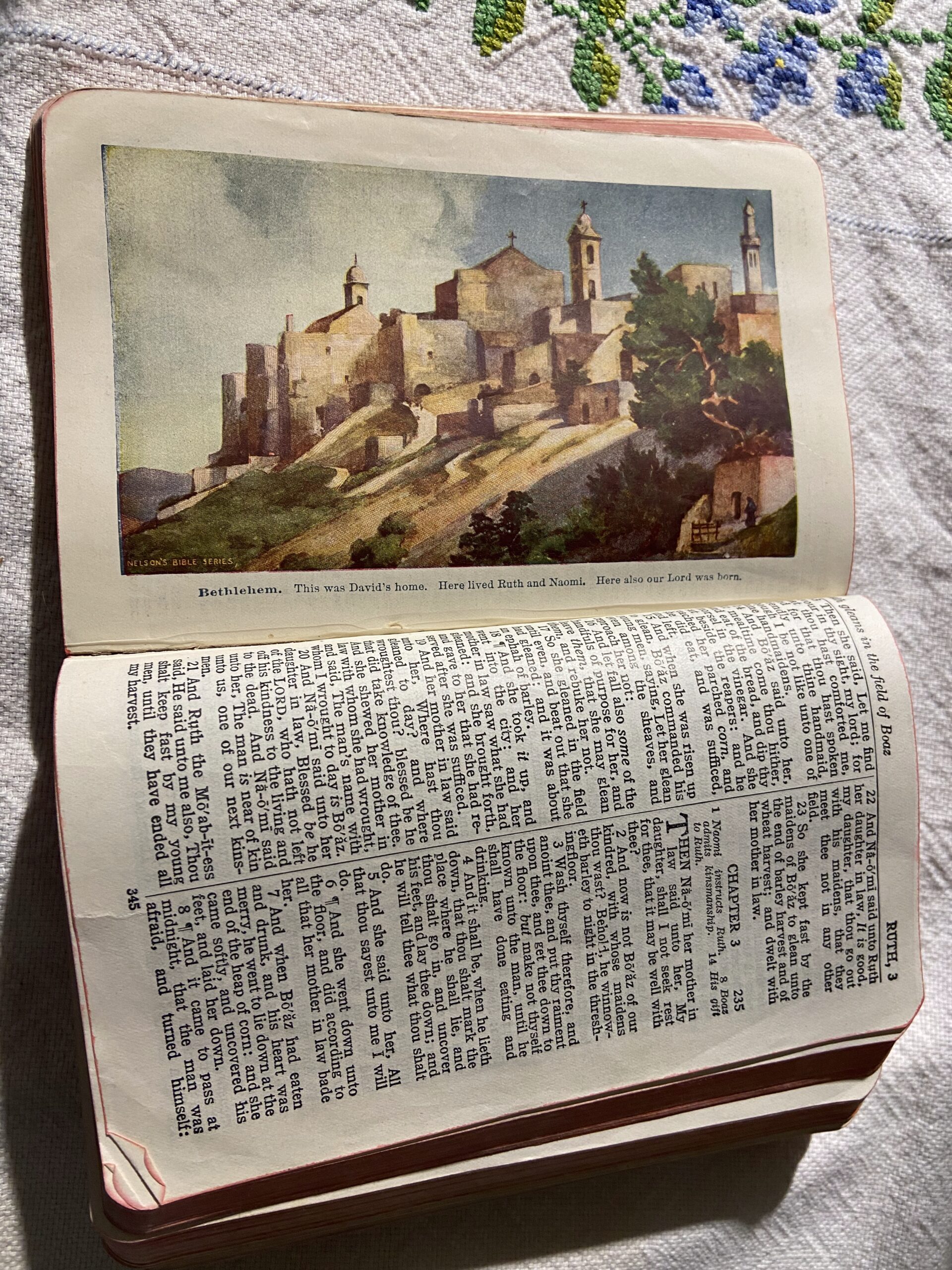

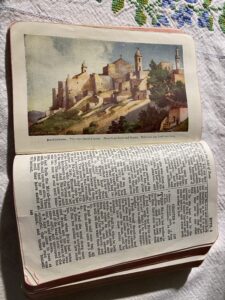

But until she was four, Mom lived with her grandmother Lisa. Lisa had been born in Finn Forest in Sweden, the oldest of Marta’s surviving children. Lisa, like Lars whom she married, almost certainly knew some Kaisa-type velhot in the woods. Lisa gardened, and Mom gardened with her. Lisa plowed up the fields and planted right alongside Lars, lifting up her skirts when the ground was muddy. Lisa gave Mom her first Bible, the one pictured above. Lisa and her sisters founded a church where the women as well as the men preached and danced and spoke in tongues. While this is decidedly Christian, it includes elements of the older Finnish traditions – women having authority equal to men, dancing as holy, and speaking in other languages (perhaps, I think, in Finnish).

Mom was introduced to gardening and gathering and making herbal concoctions by her Finnish Grandma Lisa. It was also Grandma Lisa who taught Mom that the Bible offered guidance and protection.

In both Great-grandma Lisa and in Mom, the velho was hidden. The Christian, in an unorthodox way, was allowed to be public. Maybe after death, though, the velho spirit has burned free, joined the Christian once again, hand-in-hand.

Great-Grandma Lisa seems free and wise to me when I speak with her now and seem to hear her answers. Her Bible often gives me good guidance when, oracle-style, I open it at random after asking a question.

Some time after her death, my mother appeared to me in the dream. She stood by the kitchen sink, glowing. When I asked what she was doing, she replied, “I am doing what we women have always done. I am making a potion.” That is not a word she would have used when she was alive, but in my dream she spoke it with fervent joy.

How then, do we descendants learn to be velhot, to be ones who know what we are becoming and who are at peace with the rocks and trees? How can we spring greenly from these traditions – the Christian and the velho both?