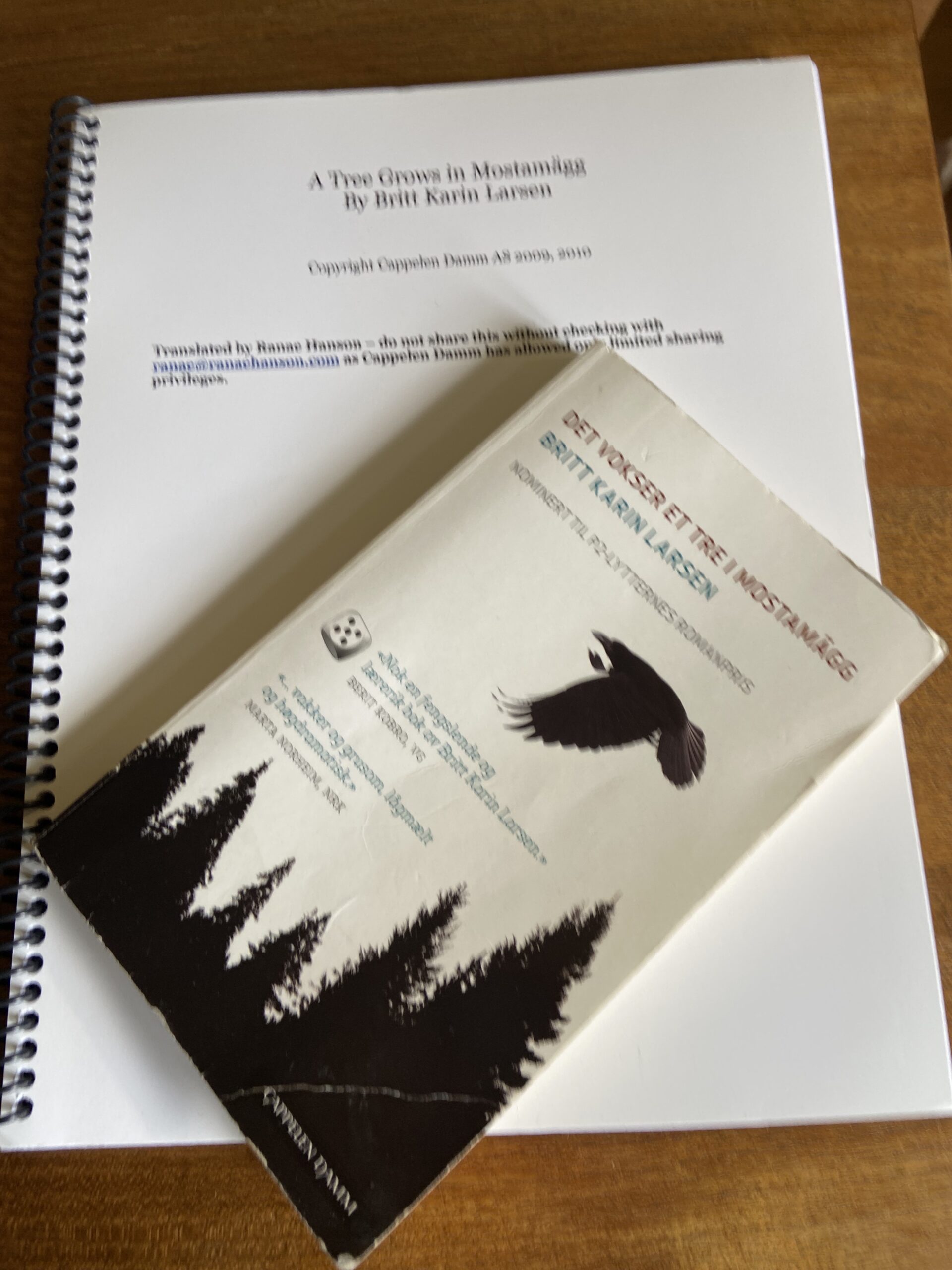

Det Vokser a Tre i Mostamägg by Britt Karin Larsen

Translated by Ranae Lenor Hanson

All rights reserved

A wanted child comes into the world, born under the tree of love.

Another child comes into the world, born under the tree of solitude, for it was not wanted. It should never have been born, and when it screams, something must be pushed into its mouth: a nipple, a finger, a rag dipped in liquor. Then it falls silent. Then again only the whisper from the tree canopy is heard, and the mother can take the child in her arms and search for a place where the trees grow denser and the shadows provide better hiding. She digs herself a home in a place where the ground is soft. For two human bodies, one yet small, the home need not be large. In villages where warm hearts are few, earth warmth has saved lives.

“Look, here she lived, in a pit in the ground.”

“That’s not true. No one can live like that!”

She digs a pit into a slope on the Swedish side of the border, enough to provide protection from the wind and rain. She shelters it with logs covered with peat and spruce bark: a wall, and at the same time a roof. In this country, no house can be without walls. But who helps her, who provides the thatch? No one. There is no one to help her. She finds old timber in the forest that she drags to the place while the child lying in the moss screams. She drinks from the stream in the valley, and she nurses, and she goes looking for birds in the snares she has set, and she looks for fish in the lakes. She doesn’t think of the future because the child may not live the winter over. The first two she lost, so why should this one live?

The quivering of life at the breast is a short-lived state. Like any other passing thing, this will not last.

The child, a girl, wails more fiercely than the last, and her little fists clench when the mother is not quick enough to get her breast out. The girl must be given a name, a name without a priest and without church bells. But is not the forest itself full of churches, and is not the sound of aspen-leaf chimes good enough?

On the next ridge is the tall stone that has been a church for more people than her. There she carries the child when it is a month old. “Troll churches” the rocks are called, and disfavor falls upon those who touch them, but is she not already out of favor? The stone does not disappear the way men or children do. The stone is faithful and patient. It has names in many languages. “Givi” it is called in hers, a word with a lightness to it and, think, do not heavy things need a light word? A word that can give a light, a boost?

Now she kneels in the moss in front of the old giant, and lifts the child up.

“Rakas Givi,” she whispers. “Dear Stone, give Annikka safety and calm! Make her strong, if she lives, and not weak like me!”

She lifts the child above her head, so the rock and the mountain and the sky and all good forces can see it. She doesn’t have to hide the child from the clouds or winds. Only from people must she hide it.

Perhaps, placed high above the others gods, Herre Jomala, the Lord God, might exist, but does He exist for such a one as her?

As a child, she had learned to pray, but the Lord didn’t give her refuge from cold the time she asked for it. The earth gave it to her and gave her leaning stones that she could crawl beneath. And the lake now feeds her. Everything the Lord denied her, she gets here in the forest. Therefore, it is to the stone and trees that she turns, the rushing wind and the clucking stream. Why should she turn to anything else?

Her god is so close she can hear and know him every time she puts her cheek to a tree. He promises her nothing, for those who promise forget it the next moment. He is like the men she has found warmth with, those who never promised her anything, for then they would be liars. Anyone who promises is a liar or later must become one.

She managed to conceal the previous child for as long as it lived, but then she was caught while she still had milk. It had wetted her garment in front, and she was held in the presence of witnesses while a trembling old priest unfastened her clothes to show her full breasts and the dripping milk.

“Here is the proof that this woman has let herself fall into lust and that she has gotten rid of the fruit of that lust!”

Disquiet remains at a place where a mother has abandoned a child. At Crying Rock people still hear whimpering at night.

She herself has never killed anyone, none except the fish and birds she has caught, and that is different. When it comes to the bird’s life or hers, there can be forgiveness.

The men in dark clothes who discovered the milk from her breasts wanted to know where she had made off with the babe. The first child no one ever knew of. She had laced herself so tightly that the rounding of her stomach could not be seen. By the pond she had hidden an old cloth which she afterwards packed with stones and lowered into the depths with the child, who had not cried. Then she had gone back to the cattle barn of the farmer whom she worked for. These were years of distress, but not about the work. She had sinned but never killed anyone. The first child was without a voice, without breath. It was Herre Jomala who had willed it thus. The child she birthed next had been drowned in a stream while she was out seeking food. The man she had gotten warmth with didn’t want to fall into disgrace. Who wishes to hurt the man who gave them warmth?

“The child’s father?” they wanted to know.

She bowed her head.

“It was so dark,” she whispered. “So dark and cold.”

“Servants at Suomägg sleep in the cattle barn in the summer. They sleep as close as herring there, women and fellows jumbled together! I guess you had plenty to choose between, then. Thus you don’t even remember who he was.”

She looked down, her heart thumping, and she narrowed her eyes hard. Now she was making herself guilty, but better to make herself seem loose than destroy a home with three young ones by speaking the truth. It was the householder himself who held her close in the dark.

He had such good hands, Heikki of Suomägg. How long could a man live without the touch of hands? How long? For the wife of Suomägg did not want any more children. Yet, she was kind to the servants. They lacked neither clothing nor food. Who wishes to hurt those who only do good?

The sounds of the animals there in the dark, the low rustle of the twisted-birch lock. The sounds of the others sleeping or waking in the cattle barn made one feel even more alone. And then: Someone came wandering between stables and cattle sheds and haybarns, because he was alone, too.

That the children who came of this were not allowed to live was probably the decision of Herre Jomala, for He had a purpose in everything, though she screamed when she found the drowned child. For that she would never, ever forgive Him. The little boy had recently lain hot against her chest and had smiled. She had thought that if the winter was too harsh and if she had no roof to crouch under, she would carry him down to the village to the house of the childless big farm owner and, under cover of night, put him, well-wrapped, on the stairs. He would have been saved, because would they let a little child die?

Now she had given birth to a third child, an angry little girl, and this child is still alive, living with her in a pit she dug for both of them. She also digs a pit for the potatoes she has taken from a field, and over them she spreads earth and moss. “Hauta” the ancients called this. That is the word for grave. One digs a grave to bury, to conceal, but also to preserve. He who looks to save life must heed the sky, what it shows, but also look for what the earth hides, even in what may resemble a grave.

The child is hers. The name of its father will not be dragged out of her, not this time either if she is caught, even if she has to confess in the church in an interrogation before everyone.

Autumn is approaching. She is freezing, but the child does not freeze. It lies under the fur blanket she took from the largest farm on this slope-side, a farm where they will hardly miss it. There is forgiveness for what one takes to save a life, if one takes only from those who have enough, who will hardly notice that something is gone. There is forgiveness then, isn’t there?

If the child born under the tree of solitude is allowed to live, there is a reason for it, but then it will need food, and the food Our Lord does not provide one must provide herself.

A drawn-out scream reaches her in the rough shelter. It is like the scream of a human, but she knows it. It’s the fox, and a fox scream means something.

She squeezes the warm bundle close to her.

“Someone is going to die tonight, Annikka, maybe an old crone who will finally find rest. But you, you shall live. You shall not die, not yet!”

When the earthen refuge she’s dug isn’t good anymore, she has to find something else. Perhaps she has already found it. Two days ago she came across an old charcoal-maker’s hut, almost like a turf hut, quite whole, but it lay twisted and seemed not to have been used for some years. There she might dare to stay for a while, when the cold begins.

The fox screams again, and she squirms anew.

Are any of her people going to die?

But who are her people?

Someone once said she had a sister. Others said there was a brother, but maybe it was just something they said because she was crying.

It’s been a long time since she cried.

Now she applies herself to life.

She has no relatives, no one to go to. Winter is at the door, and one who wants to save a life then, with no one to go to, has no time to cry.